Did you catch this review?

1.) The French artist Edouard Vuillard (1868-1940), a well-kept secret

(Read review at melaniekijktkunst.nl)

2.) Burlington Magazine: Review of Venus Betrayed by Belinda Thomson, March 2021

(Read review by scrolling down)

Venus Betrayed: The Private World of Edouard Vuillard

By Julia Frey. 424 pp. incl. 220 col. + 40 b. & w. ills. (Reaktion Books, London, 2019), £39.95. ISBN 978–1–78914–160–3.

Being neither a conventional biography nor an expanded life and times, this book is difficult to categorise, something its enigmatic title and subtitle do their best to convey. Many aspects of Edouard Vuillard’s work are largely left out of account: the still lifes, for instance; the landscapes and seascapes; even the large- scale decorative panels. Instead, Julia Frey confines herself to dealing with Vuillard’s social paintings over the course of seventeen discrete essays, exploring a variety of themes via playfully allusive or provocative titles such as ‘Missing Men’, ‘The Corset Factory’ and ‘Pregnant Silences’. The eponymous ‘Venus Betrayed’ chapter focuses on a group of paintings of the Paris apartment Vuillard shared for the longest time with his mother, whose mantelpiece was dominated by a life-size truncated plaster cast of the Venus de Milo. With sly humour, the artist contrived to set his Venus off against his ostensible subject, be it his elderly, now diminutive mother kneeling like ‘his scullery maid’ in front of a recalcitrant ‘Mirus’ stove or his statuesque painter friend Madame Val Synave surveying the loss of her Renoiresque beauty in front of the mirror. Over the course of his life and his often- unsatisfactory entanglements with women (more numerous than one hitherto realised), Frey wonders archly whether Vuillard betrayed Venus, or Venus betrayed him.

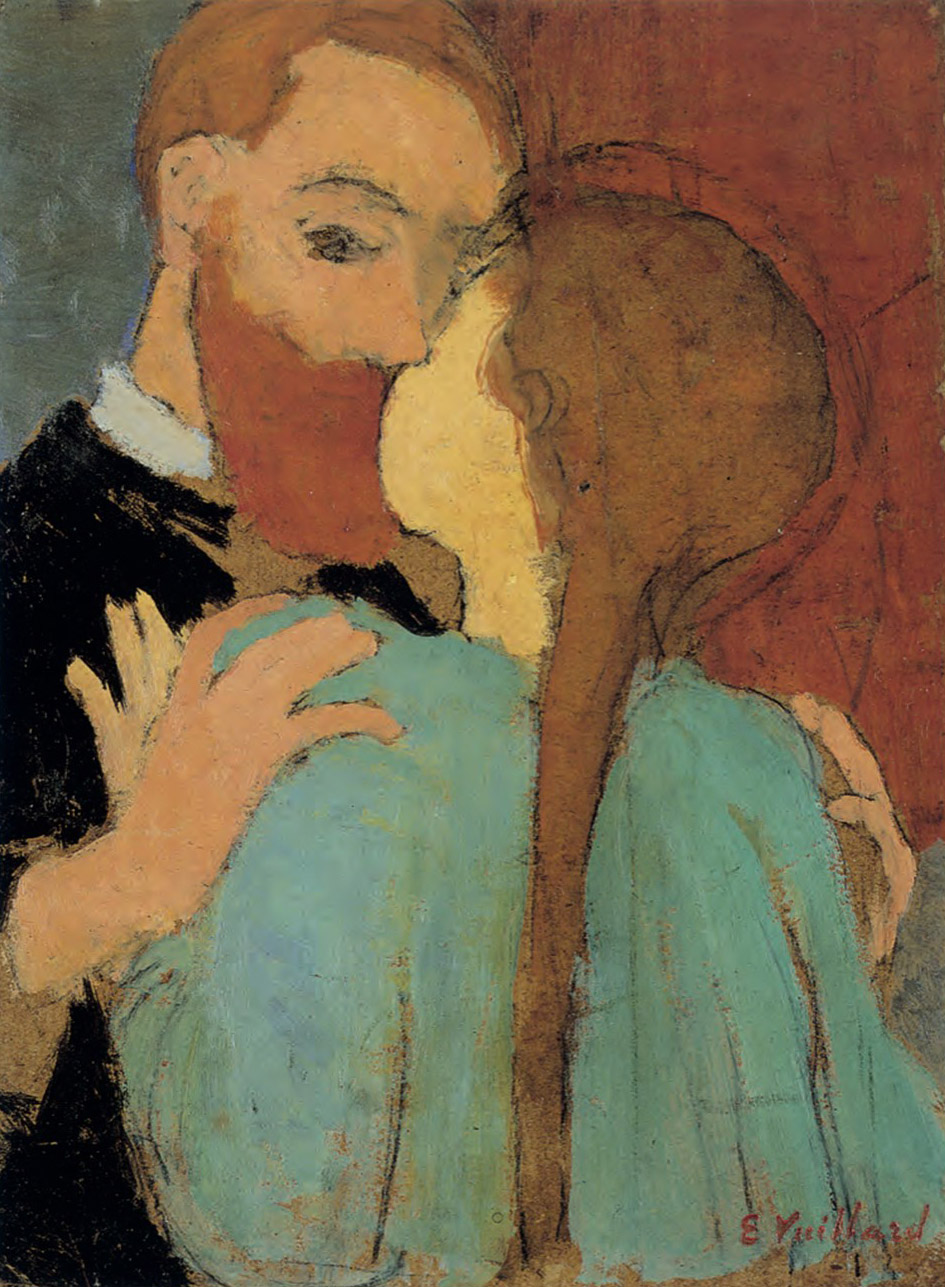

Frey’s carefully probing, sometimes forensic readings study Vuillard’s journal and unpublished correspondence on the one hand and images ranging from thumbnail sketches to paintings on the other; her take, avowedly informed by psychotherapy, yields considerable insights. Thus we meet forthright judgments of Vuillard’s personality such as: ‘like many reticent people, behind a modest and subdued appearance Vuillard was arrogant and deeply ambitious’ (p.41); and elsewhere, ‘paralysing ambivalence dominated him; he was completely unable to take a firm stand’ (p.11). Occasionally when applied to an art so inseparable from ambiguity, the approach, for this reader, sometimes veers towards the over- categorical, reading into rather than out of the evidence. A case in point is her interpretation of The kiss (Fig.7), a small, synthetic study of Vuillard embracing a pigtailed young woman. The 2003 catalogue raisonné by Guy Cogeval and Antoine Salomon pointed out the flaws in the figure’s traditional identification as the artist’s sister Mimi, proposing instead an unnamed seamstress. Frey elaborates, positing a lower-class girl Vuillard had fallen for and seeing the pentimenti that reduce the size of her head as ‘effectively emphasising her smallness and vulnerability, but also perhaps his need to reject her power over him’ (p.148). Perhaps, indeed. But she may well be right in seeing possible signs of a pregnant apprentice among his early puppet-like female studies, and the comparison she infers between Vuillard’s purported withdrawal from such a lover and his mother’s emotive reaction in 1908 to seeing Gustave Geffroy’s hard-hitting naturalist play L’Apprentie, which triggered for Vuillard painful memories of some earlier drama involving a girl from Marseille, is evidence of brilliant detective work.

The nature of the relationship between Vuillard the devoted son and his self-effacing corsetière Maman has been increasingly questioned of late.1 For Frey, too, that tender mother-son image masked a forceful if not tyrannical matriarch and a rebelliously wayward son whose perceived sins continued well beyond his youth since he persisted in living beyond his means and mixing with a fast set. The bolshily submissive yet devoted love Vuillard felt for his mother, seen in the numerous, often unsparing images he made of her, prefigure, Frey argues, his repeated attachments to unattainable, domineering women such as Misia Natanson and Lucie Hessel. She also turns her attention to the previously unconsidered lives of Vuillard’s maternal grandmother, Désirée, and his sister Mimi. A particularly telling suggestion is that the shame of being born out of wedlock, even though her parents subsequently married, left Vuillard’s mother with a lifelong sense of social inferiority and fear of history repeating itself. That in turn soured relations with her daughter Mimi, whose superior boarding- school education (free to the daughters of holders of the Légion d’honneur) ill-fitted her for the humiliations of life in the sewing studio. Vuillard’s troubled relations with his seductive but amoral brother-in-law Ker-Xavier Roussel, first unveiled in the Cogeval-Salomon catalogue raisonné, are examined here in excruciating detail. Rather than seeing Vuillard as the manipulator of the situation as Cogeval does, Frey paints Roussel as an irresponsible egotist who made enormous demands of Vuillard. She is perhaps unduly dismissive in describing Roussel’s œuvre as ‘mostly forgotten today’ – in fact there have been three monographic exhibitions devoted to it over the past decade alone – and the problem of finish and the ‘non- fini’ that beset him was one shared by many artists responsive to Impressionism, including Bonnard and Vuillard.

With its focus on Vuillard’s private world, Venus Betrayed largely excludes aesthetic questions. Although the stimulating exchange of intellectual and political ideas among former Condorcet pupils is well characterised, the Nabi enterprise, forcing Vuillard to radically rethink his earlier naturalism before steadily retrieving it – a process that surely affected his art for much longer than the year or so Frey allows – is rather downplayed. There is no mention of the soul-searching exchange Vuillard had in 1898 with his close friend Maurice Denis, whose social and cultural origins were similar but from whom he was severed by the Dreyfus Affair (Denis was an anti-Dreyfusard). Only the final chapter, ‘Repainting’, is devoted exclusively to matters of technique and the revisions Vuillard went in for, which to an extent, viewers found and still find disconcerting.

Nevertheless, Venus Betrayed is lively and well crafted, a distillation of exhaustive looking and careful thought. Building imaginatively upon the foundations of recent scholarship – the 2003 catalogue raisonné and a trio of French studies analysing Vuillard’s journal2 – it deserves to be widely read. A thought-provoking addition to the study of an extremely complex individual, Frey’s book affirms the value of exploring the relationship between an artist’s private life and creativity.

1 See, for example, A. Salomon and G. Cogeval: Edouard Vuillard: The Inexhaustible Glance, Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings and Pastels, Paris 2003; and F. Berry and M. Chivot: exh. cat. Maman: Vuillard and Madame Vuillard, Birmingham (Barber Institute of Fine Arts) 2018–19.

2 M.Court:‘Vuillard,lesannéesdejeunessevues à travers les carnets de l’Institut: transcription’, unpublished MA diss. (Université Blaise Pascal Clermont-Ferrand 2, 1992); F. Alexandre: ‘Edouard Vuillard: (1888–1905 et 1er janvier 1914–11 novembre 1918): édition critique avec présentation, notes, annexes et bibliographie’, unpublished PhD diss. (Université de Paris VIII, 1998); and J. Girart: ‘Le Journal d’Edouard Vuillard (1868–1940), 1er novembre 1907–31 décembre 1913: transcription’, unpublished MA diss. (Université de Paris I, 2001).

299-300 the burlington magazine | 163 | march 2021